Until recently, Americans spent around 10%, and Europeans 12%, of their incomes on food from grocery stores and restaurants. But recently, those purchases were made much more difficult by disruptions in the food supply chain and a reduction in many people’s incomes. Shortages and long lines at grocery stores have also stoked concerns about our food security. But one positive response is a heightened interest in growing our own food, as part of a movement toward self-reliance.

Seed supply companies are seeing an unprecedented uptick in sales. And backyard gardening information is in such high demand that the National Gardening Association created a Guide to Gardening During a Pandemic.

But if you want to grow your own food, where do you start, especially if you’re a gardening newbie? There are so many different types of vegetables to grow. And not everyone has the same growing conditions. Luckily, you can find, or create, your own planting calendar, which will help you determine what to plant when, so you can successfully grow your own food.

What Is a Planting Calendar?

A planting calendar, or planting schedule, shows you what to plant during what time of year, depending on your location. Most planting calendars use frost dates (the last spring frost and first fall frost), which provide guidance on whether to sow seeds indoors or outdoors and when to stick those seeds in the ground or transplant seedlings.

The following sections cover what to consider when determining what to plant and when to plant it, as well as introducing you to the different elements of a planting calendar.

Planting Zones

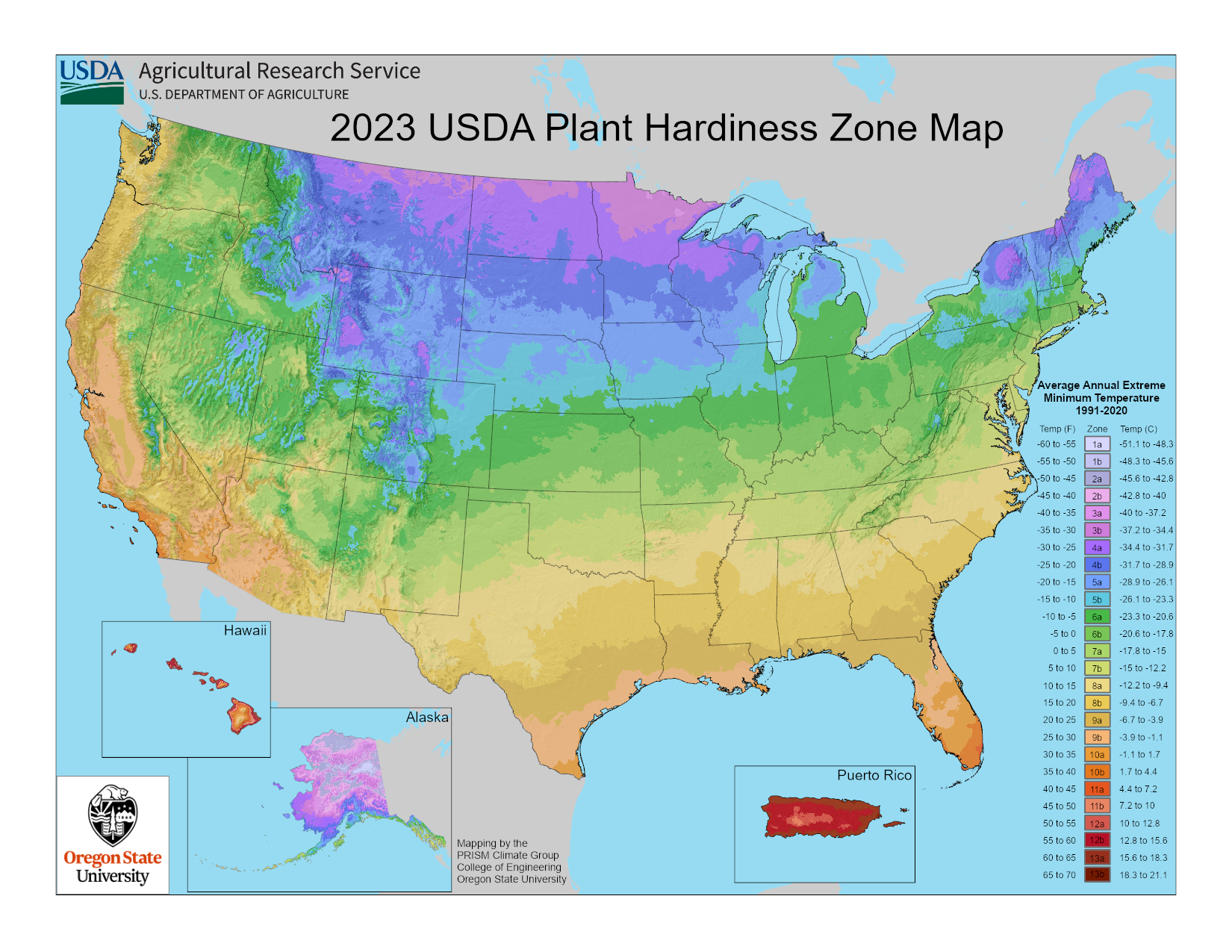

One of the first elements you’ll need to determine if you want to grow your own food is your planting zone. A planting zone, or hardiness zone as they’re sometimes called, is a geographical area where certain kinds of plants can grow based on the region’s climate conditions.

In the US, planting zone standardization comes from the USDA’s Plant Hardiness Zone Map. This map divides the US into 10-degree zones based on the average annual minimum temperature during the winter. The continental US has 10 main zones, with an additional three zones for Puerto Rico and Hawaii. You can find your planting zone by looking at the map above or visiting the USDA’s site here.

Note: If you consult an old gardening book or magazine that references the USDA zone map, you may be using outdated information. The zone map was updated in 2023 to reflect better collection methods of temperature data as well as climate change. So you still have to use a little judgment in deciding when to put different plants in the ground.

Although this is a US-based system, it’s used around the world to determine planting zones. In the UK, the Royal Horticulture Society has also come up with its own system. They use USDA zones six through 13 and assign them their own hardiness ratings. Other countries can find their hardiness zone by determining their coldest winter temperature and comparing it to the USDA zone map.

Once you find your planting zone, you can then move on to determining what you can plant, based on your zone.

What Should I Plant?

What you plant should be based on what you want to harvest and eat — provided it can grow in your zone. And, there are a few things to consider before buying seeds or baby starter plants.

Nutrition Per Acre

When it comes to nutrition, home gardens are the champs. Growing food at home is an extraordinary way to enhance food security and self-reliance. And it’s also a great way to contribute to carbon sequestration and soil regeneration, and to boost your family’s vegetable intake. Some of the top nutritional foods that many people like to grow at home are:

- Tomatoes – One medium tomato includes 40% of your daily vitamin C and 20% of your vitamin A.

- Cucumbers – Cucumbers are mostly water and are a great hydration source. They also contain over 60% of your daily vitamin K.

- Sweet Peppers – Sweet bell peppers are one of the richest dietary sources of vitamin C and contain a number of disease-fighting antioxidants.

- Green Beans – Are a helpful source of protein, folate, and a number of other vitamins and minerals.

- Carrots – 100g of carrots (or the equivalent of two small or medium-sized carrots) have nearly three times your daily vitamin A, an important nutrient for eye health and the immune system.

- Summer Squash – One cup of chopped summer squash or zucchini contains vitamins and minerals such as vitamin C, riboflavin, B6, and manganese.

- Onions – Onions contain organosulfur compounds, which are antiviral, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory. One onion also contains about 10% of your daily recommended fiber, making them good for gut health too.

- Hot Peppers – Like sweet peppers, hot peppers are high in vitamin C and antioxidants. They also contain over 11% of daily B6 per pepper, which is a vital nutrient for the nervous system.

- Lettuce – Lettuce might not contain a lot of protein or calories, but it’s surprisingly dense in micronutrients. Most types of lettuce are good sources of vitamins A, C, K, and folate.

- Peas – Peas are an excellent source of plant-based protein and fiber (over ⅓ your RDI of fiber per cup!).

- Sweet Corn – 100g or about ⅔ cup of corn provides 9.4g of protein, 7.3g of fiber, and is high in minerals like magnesium, manganese, and selenium, among others.

All of these foods have unique and powerful health benefits. And they’re all pretty tasty, too!

Seasonal Produce

Along with growing foods that you or your family will enjoy, and that are high in nutrition, it’s also a good idea to check what crops can do well in your region.

The USDA’s seasonal produce guide gives a general overview of produce by season. But you can also input your state and a specific crop you’d like to plant. And this tool will tell you when and if it’s ever in season where you live. Keep in mind, the seasons listed are not necessarily when you would plant, but rather when they’d be available after harvesting.

Also, if you live in an area with lots of small local farms, you may not want to reproduce the crops that you can buy from them. What’s available locally is a pretty good indication of what may grow most easily in your region. You may want to focus especially on less common heirloom varieties. Or on some of the more expensive fruits and vegetables that you might not buy regularly, on account of their cost. But especially if you’re new to gardening, it never hurts to go with standbys that are prolific and relatively easy. For example, many people find that zucchini, tomatoes, onions, and cabbage are especially easy to grow. And there’s nothing like success to build confidence!

When Should I Plant?

Determining when to plant seeds ultimately depends on your planting zone, what season the crop thrives in, and how long it takes the crop to come to maturity. Most zones should plant in spring or early fall. However, there are hardier vegetables like potatoes and other tubers that can last through the winter in some areas, especially if you cover them with layers of insulating mulch before the first frost. And fruits and vegetables that do well in hot weather can sometimes be planted in the summer.

If you already have seed packets at home, you might notice that some of them contain information such as hardiness zones, when to plant and harvest, how long they might take to be ready for harvest, and other important growing information that can inform or complement your planting calendar.

The length of time it takes to grow vegetables varies but can range anywhere from a few weeks to a few months. If your goal is to provide enough food to feed your family regularly, it’s always best to plant as soon as possible. By following the seed specifications, you can give yourself the longest possible growing season.

Planting Indoors or Outdoors?

Not all seeds need to or should go straight into the ground or a container garden. Depending on what you’re planting and your planting zone, starting indoors in flats or small pots might be a better option. Some plants suffer when transplanted. Others benefit from germinating indoors in a controlled setting. However, there often aren’t hard-and-fast rules about what you can start indoors versus outdoors. This is when a planting calendar really comes in handy as many show when to sow seeds indoors, when to transplant those seedlings into the soil, or when to sow the seeds directly into your garden bed.

Indoors

The main benefit of growing seeds indoors is a controlled environment. Your seedlings are not at the mercy of Mother Nature and have a better chance to start their lives as healthy plants. Starting seeds indoors allows you to get a head start on the growing season. This is especially beneficial if you live in an area with a short growing season (namely cold regions).

Some ways you can grow seeds indoors are:

- By using grow lights

- Hydroponically

- In a greenhouse

- In containers on a sunny windowsill

If you intend to start indoors and then transplant, plan on starting your seeds six to eight weeks before you’ll be transplanting them (for spring plantings, transplanting should happen only after the last frost). Remember, some plants don’t like to be disturbed once planted and therefore aren’t good candidates for transplanting. Typically, these are underground crops with sensitive roots like beets, carrots, and turnips.

After you’ve started your seeds and your seedlings have matured sufficiently, you can transplant them directly into the ground or continue to grow them in a container garden. One trick to transplanting is to make sure you pack the garden soil tightly around the clump of dirt surrounding the seedling. Doing so prevents air pockets that can impede the flow of water and nutrients, preventing the fragile young roots from establishing themselves in their new garden home.

Outdoors

In general, seed germination rates are higher, and the process occurs faster, when it’s warmer. Therefore, starting seeds outdoors is best in warmer climates with a longer growing season. Or during warmer parts of the year in colder planting zones (such as when planting summer vegetables).

When planting outdoors, you can sow your seeds directly or transplant indoor seedlings into the ground. Seeding straight into the soil is good for fast-growing and early season veggies like lettuce, kale, and beans.

If you choose the transplant route, make sure the crop you’re choosing is easily transplantable. Checking the seed packet or plant calendar will often give you this information. When you do transplant crops, however, it’s a good idea to “harden them off” before planting them straight into the ground. This consists of gradually exposing the seedlings to outdoor conditions by slowing down watering and controlling the amount of light they receive throughout the day. While it may seem counterintuitive, excessively coddled seedlings don’t typically turn into healthy adult plants.

Where to Find a Planting Calendar

Many different plant calendars exist online, and they’re all pretty similar. So whichever one you use will become a matter of personal preference. A couple of excellent options to start with, for folks in North America, are the Farmer’s Almanac Planting Calendar and The National Gardening Association Planting Calendar.

After you enter your location, these calendars will show you what kinds of crops to plant in either spring or fall, frost dates, and whether you should start seeds indoors or outdoors.

Creating Your Own Planting Calendar

If pen and paper is more your style, you can always create your own planting calendar from scratch. To do so, you’ll need:

- Pen or pencil

- A paper calendar that you can write on (or draw out your own)

- Seed packets

- Your planting zone

Step 1: Determine your last frost date for spring, based on your planting zone and zip code. You can do so by looking it up online, in a gardening book, or perhaps (in the US) by calling your local Cooperative Extension office.

Step 2: Mark your frost date on the calendar.

Step 3: Next, make a list of all the crops you want to plant (and have seed packets for).

Step 4: Then, take the seed packets and look for whether it’s recommended to start indoors or outdoors. Write this information next to your list of crops.

Step 5: From there, you can start marking on your calendar when to start or sow your seeds (and when to transplant, if applicable). To do so, you’ll need to use your frost date as a marker. And then, you’ll need to add a week or two of buffer (in case of a later than usual frost). For later season crops that will grow into the fall, you’ll count backward the number of days it takes for the crop to reach maturity. And for warmer season crops that you’ll plant in springtime, you’ll want to count forward. You can also find this information on your seed packets.

If you’re more tech-inclined, you can also try your hand at creating a plant calendar on your computer. You can use a spreadsheet or online template like this one from blogger Better Hens and Gardens.

Happy Planting!

Determining what’s best to plant when ultimately depends on where you live (along with some personal preference on crops). When it comes to planting calendars, use what’s best for you. Try one of the online or pen and paper methods mentioned here, or come up with your own.

Just don’t make the perfect into the enemy of the good. If you can’t do all you want, or don’t have the perfect timing, don’t let that stop you from giving some crops a try. Remember, frost will kill a lot of plants. So don’t plant too late if you’re in a place with cold winters. Here’s to the fruits (and veggies) of your labor!

Tell us in the comments:

- Have you ever grown or do you intend to grow any of your own food?

- Do you use a planting calendar?

- What are your favorite foods to grow?

Featured Image: iStock.com/FatCamera

Read Next: