At the Battle of Waterloo, Napoleon Bonaparte faced a combined British and Prussian force led by Wellington and von Blücher. Outmaneuvered and outgunned, Napoleon would flee the field, abdicate his throne, and die in miserable exile.

For two centuries, historians have debated what went wrong. What caused the master of the battlefield to underestimate his foes, commit so many errors, and fall so completely into their traps?

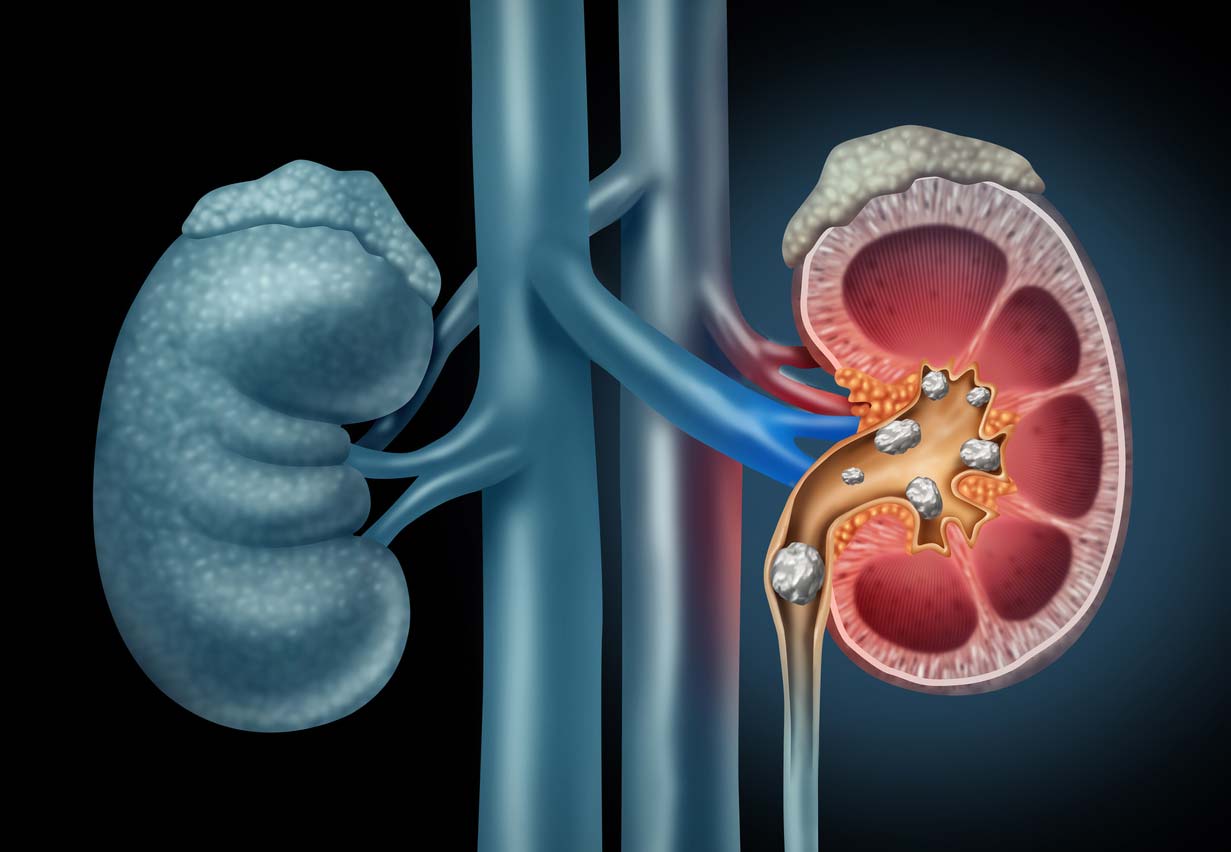

The answer may have been kidney stones. Apparently, Napoleon suffered from kidney disease for most of his life. And during the Battle of Waterloo, his body was dealing with a particularly nasty kidney stone that rendered him “lethargic and indecisive” — precisely when he needed his full mental vigor.

Need more proof? Well, almonds are one of the foods highest in oxalates — compounds that may contribute to kidney stone formation. And guess what Napoleon’s favorite food was? According to his second valet, “What he especially liked were fresh almonds. He was so fond of them that he would eat almost the whole plate.”

Should You Avoid Oxalates?

Which brings me to today’s topic: oxalates in food. Thanks to some prominent “alt-health” voices and the speed of internet rumors, oxalates are sometimes demonized as nutritional villains, along with other supposedly harmful compounds found in plants, such as phytates, lectins, and the alkaloids found in nightshades. The main concern is that eating a diet high in oxalates can lead to the formation of kidney stones. Another fear is that oxalates act as “anti-nutrients,” impairing the absorption of minerals like zinc, calcium, and iron.

But what’s the truth about oxalates? Are they really that bad? Will a fondness for almonds cause you to lose world-shaping military campaigns? And should you avoid oxalate-containing foods, whether you’re prone to kidney stones or not?

What Are Oxalates?

While the terms oxalate and oxalic acid are often used interchangeably, they’re not the same. Oxalates are salts that form from oxalic acid, a naturally occurring organic acid found in plants, animals, bacteria, and fungi.

Plants manufacture oxalates for their own purposes — mainly to protect themselves against insects and other herbivores. But the same characteristics that make oxalates annoying to predators — like binding calcium and other minerals — provide health benefits to people when we eat oxalate-rich plant foods.

Oxalates play a role in calcium regulation, ionic balances, and heavy metal detoxification. While some of the oxalates we carry around in our bodies come from eating plant foods that contain them, our bodies can synthesize them as well.

What Foods Contain Oxalates?

Oxalates are found in a variety of plant foods, like nuts, beans, and some vegetables.

Dietary sources of oxalates for some foods are listed below, along with the average amount of oxalates in a 100-gram serving.

- Rhubarb, raw — 1,060 mg

- Spinach, raw — 650 to 1,290 mg (varies by variety)

- Spinach, cooked — 755 mg (about ½ cup)

- Swiss chard, raw — 657 mg

- Almonds — 369 mg

- Dark chocolate — 232 mg

- Peanuts — 131 mg

- Sweet potato, baked or broiled — 126 mg

- Black beans, cooked — 60 mg

- Beets, boiled, steamed, or pickled — 57 mg

- Potatoes, baked, with skin — 46mg

Despite — or perhaps because of — their oxalate content, these are some of the healthiest foods on the planet, whose consumption is associated with longer life expectancy.

A well-balanced diet that incorporates a good variety of healthy foods is going to contain its fair share of oxalates and other “anti-nutrients.” However, it will also include an array of healthy compounds and nutrients that can help counteract any potentially problematic effects.

If these types of foods contained just oxalates, that would be a problem. But the presence of potassium, calcium, and a whole range of phytochemicals found in oxalate-rich foods means that dietary oxalates are not an issue for most people.

Oxalates & Kidney Stones

The kidney stones that contributed to Napoleon’s demise may have come (in part) from his almond consumption. But the medical field wasn’t quite as developed back then as it is today. And in the modern world, research is telling us that while high oxalate foods may contribute to the formation of some kidney stones, there are other factors that may be at least as significant.

It turns out that there are four basic types of kidney stones:

- Calcium phosphate kidney stones mainly result from animal protein-rich foods like meat, dairy, and eggs; fruit juices, sodas, and processed foods with added phosphorus; and excess sodium.

- Uric acid kidney stones are a result of too much acid in the urine. And they are mainly fueled by animal protein, sugary drinks, and alcohol.

- Cystine kidney stones are caused by a hereditary condition that causes cystine to leak into the urine. Research indicates that they can be fueled by drinking too little water, consuming too much sodium, and eating animal protein.

- Calcium oxalate kidney stones are the most common kind of kidney stone. They form when calcium in your urine combines with oxalates. Low-oxalate diets are sometimes prescribed for people who are prone to the calcium oxalate form of kidney stones. Adhering to such a diet generally means eating less than 100 mg of oxalic acid per day — which means no spinach (or beet greens or Swiss chard). When this diet is prescribed, it’s usually out of an abundance of caution because the role of dietary oxalates and calcium oxalate kidney stone formation is still inconclusive.

If you’re concerned about kidney stones, there is only one type that may be linked to oxalate consumption. However, oxalates don’t just come from the food you eat. About half the oxalates in your urine come from endogenous synthesis (which is a fancy way of saying that your body makes it by itself).

What causes your body to make oxalates endogenously? Researchers believe that salt, animal protein, and excessive vitamin C are all associated with increased oxalate formation in your body, as measured by what winds up in your urine.

Is Oxalate an Anti-Nutrient?

Oxalates can also bind to certain minerals in the gut, especially calcium, zinc, and magnesium, and prevent them from being readily absorbed. This is why it’s often considered an anti-nutrient. And is one reason why spinach, despite being high in iron and calcium, isn’t usually the best dietary source of these nutrients. Its high oxalate content can reduce the bioavailability of some of the minerals it contains.

So if you’re concerned about your calcium, zinc, or magnesium levels, you may want to moderate your oxalate consumption, and/or make sure you are eating plenty of these minerals from sources that aren’t especially high in oxalates. This is especially true with calcium because it can regulate dietary oxalate absorption. And low-calcium diets have been shown to increase the risk of calcium oxalate kidney stones.

Are Oxalates Dangerous?

Some people have gone so far as to label oxalates a toxin. It’s true that in very high amounts, oxalic acid could cause damage to your esophagus. They could even be fatal by lowering the calcium in your body to critical levels, if you were to consume household cleaning products or antifreeze that contained pure oxalic acid.

But I’m going to go out on a limb and say that most people aren’t chugging Prestone. Anyway, demonizing spinach because you shouldn’t drink antifreeze is like saying that drinking water is dangerous because someone could drown in a lake.

An average single serving (two cups raw or one cup cooked) of a high-oxalate food is not enough to cause problems for most people. If you enjoy green smoothies, note that oxalates do absorb more rapidly in liquid form.

And while I certainly advocate eating your greens (and other healthy plant foods), it’s best to make sure that some of them are lower-oxalate greens, such as kale, collards, broccoli, arugula, romaine lettuce, parsley — frankly, any green that isn’t spinach, chard, or beet greens.

In other words, if you are consuming green smoothies, green juices, giant green salads daily, and cooked greens, it’s recommended not to use spinach, chard, or beet greens every day and to limit them to 25% of your green intake. You’ll get the extra benefit of higher availability of calcium from the lower-oxalate greens.

Who Should Avoid or Limit Oxalates?

While oxalates included as a part of a balanced diet aren’t going to be problematic for most people, certain populations may benefit from avoiding or minimizing their intake.

People With a History of Calcium Oxalate Kidney Stones

First, people with a history of calcium oxalate kidney stones or kidney disease may want to watch their oxalate intake. People who suffer from hyperoxaluria, a genetic condition that leads to too much oxalate in their urine, should also moderate their consumption of high oxalate foods. If their concentration of urinary oxalates becomes too high, people with hyperoxaluria are at risk for calcium oxalate kidney stones.

People With Mineral Deficiencies

Folks at a higher risk for nutritional deficiencies (particularly minerals) may want to minimize oxalate intake. Because oxalates bind to minerals, if you’re deficient in calcium, zinc, or magnesium already, consistently eating a lot of high-oxalate foods may worsen your deficiency. This is more of a concern with calcium deficiency, since calcium helps your body excrete oxalates. Some research suggests that oxalate intake doesn’t seem to impact your ability to absorb iron.

People With Hyperparathyroid Disease

Hyperparathyroid disease is a condition in which your body produces too much parathyroid hormone (PTH). This can lead to a loss of calcium. And a diet high in oxalates, which can bind to calcium, can make already low levels of this critical nutrient even lower. For this reason, people with hyperparathyroid disease may want to avoid oxalate-rich foods.

People With Gut Malabsorption Issues

People with gut malabsorption issues — like short bowel, malabsorptive bowel disease, or celiac disease — may benefit from a lower-oxalate diet. In many cases, there may be too few bacteria present in their digestive tract to degrade oxalates sufficiently. This can also be an issue for people who have undergone bariatric surgery for obesity, since that change to the gastrointestinal system may impact the absorption of certain nutrients.

Rare Cases

There are rare instances where eating too much oxalate-rich food can lead to severe kidney disease in people with certain health conditions.

For people with high blood pressure or sensitive kidneys, going overboard on nuts and seeds can backfire. One woman, trying to manage digestive issues with a plant-based diet, consumed large amounts of oxalate-rich almonds and chia seeds daily. Over time, her kidney function declined. Fortunately, when she shifted to a lower-oxalate diet, her health began to improve.

A woman who had undergone a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery began a 10-day “green smoothie cleanse,” consuming large quantities of spinach and other leafy greens. Midway through the cleanse, she developed acute kidney injury. Once she stopped the high-oxalate diet, her condition began to improve.

A man with diabetes and high blood pressure began drinking large quantities of vegetable juices made from spinach, Swiss chard, and other leafy greens. Over time, the overload severely damaged his kidneys, eventually leading to end-stage kidney failure. He now requires long-term dialysis.

How to Reduce Oxalates in Food

If you fall into a category that requires more awareness of oxalate-containing foods in your diet, or just want to exercise caution, here are some tips to reduce dietary oxalates.

1. Consume Calcium Alongside High-Oxalate Foods

A normal calcium diet, which contains around 800–1,000 milligrams per day, should be able to offset the potential effects of oxalates that can otherwise lower your calcium levels. For more on calcium, click here.

2. Increase Your Intake of Magnesium

Magnesium can also help reduce oxalate absorption when taken at around the same time as high-oxalate foods. These effects disappear if your intake of magnesium and oxalate is separated by 12 hours or more. You can achieve this by increasing your intake of magnesium-rich foods — such as whole grains, legumes, low-oxalate nuts, seeds, and greens — or by taking a supplement. For more on magnesium, click here.

3. Cook Oxalate-Rich Foods Before Eating Them

Research suggests that boiling and steaming can significantly reduce oxalate content. One study found that boiling reduced oxalates in raw vegetables by 30–87%, and steaming reduced them by 5–53%. Roasting, grilling, or baking, however, may have little to no effect.

4. Soak, Sprout, or Ferment Oxalate-Rich Foods Before Cooking Them

A 2018 study found that soaking pulses (the edible seeds of plants in the legume family) before cooking significantly reduced oxalate levels. The researchers found that approximately 24–72% of total oxalates in pulses appeared to be soluble, meaning their concentrations dissolved in water.

Another study found that fermenting chard significantly lowered its oxalate content. Sprouting may also reduce oxalate content by up to 80% in red kidney beans. It’s important to cook kidney beans well, even if you sprout them, because cooking destroys a type of lectin called phytohaemagglutinin, which can be toxic.

5. Drink Enough Fluids

Staying hydrated with water can also help flush out oxalates and prevent dehydration, which can otherwise play a role in kidney stone formation for some people.

There’s No Need to Fear Oxalates

While some people may need to avoid dietary oxalates, particularly in large amounts, most people do not need to worry. In fact, many oxalate-containing foods are some of the healthiest foods out there.

If you’re still concerned about oxalates, there are several effective ways to mitigate their impact, allowing you to continue enjoying the nutritious foods that contain them.

In other words, you can eat almonds and still conquer all of Europe, although I can’t imagine why you’d want to. Instead, perhaps eat oxalate-containing foods in moderation (sticking to a standard serving) and work towards a sustainable and just food system for all.

Tell us in the comments:

- What oxalate-rich foods are part of your regular diet?

- What do you think about the controversy around oxalates and other anti-nutrients?

- How do you prepare plant foods to reduce their oxalate content?

Feature image: iStock.com/Teleginatania