Imagine if a pharmaceutical company came up with a truly effective drug for dementia — one that could prevent the disease in many people, and slow its progression in others. Millions of lives would be improved immeasurably, and the investors in that company would become very rich indeed.

Sadly, most of the drugs intended to treat dementia and Alzheimer’s have not lived up to their promise. While there have been some recent breakthroughs, the new drugs still don’t prevent the onset of cognitive decline. Instead, the most effective, such as lecanemab (sold under the brand name Leqembi), appear to only slightly slow its progression, while carrying significant side effects

Exercise isn’t a pill, so it can’t be patented. But while that makes it far less marketable, it’s no less remarkable. We’ve known for millennia that lifestyle plays a major role in the development (or not) of chronic disease. And studies conducted over the past half-century show conclusively that exercise is one of the best lifestyle tools for healthy aging and the prevention and management of a wide variety of conditions and diseases such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis, stroke — and dementia.

Prevention of that last one, dementia, has a particularly strong association with exercise. Alzheimer’s organizations recommend exercise as a means to reduce the risk of the disease. And it can also be beneficial for people already living with the disease.

So, how does exercise impact the brain in such a positive way? What do the studies really say about dementia and Alzheimer’s prevention and management? And are there any particular exercises that are most beneficial for dementia?

What Is Dementia?

Dementia is an umbrella term for a series of progressive neurological conditions. It involves loss of the ability to think, remember, and reason — and sometimes to control emotions and behaviors. Changes in certain brain regions cause neurons (nerve cells) and their connections to stop working properly. For the most part, the actual causes of dementia are unknown.

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, but it isn’t the only kind. Other types of dementia include frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia, vascular dementia, Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD), and Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease.

While there’s no cure for dementia, medications and lifestyle modifications can slow disease progression. Lifestyle strategies can also reduce the risk of disease development, sometimes in significant ways. Let’s look at what the research says about one lifestyle strategy in particular: physical activity.

The Research on Exercise and Dementia

Because researchers aren’t sure what causes Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia, they’re uncertain about how exercise works to prevent it, slow its progression, and even improve cognitive functions in patients with Alzheimer’s.

But work it does.

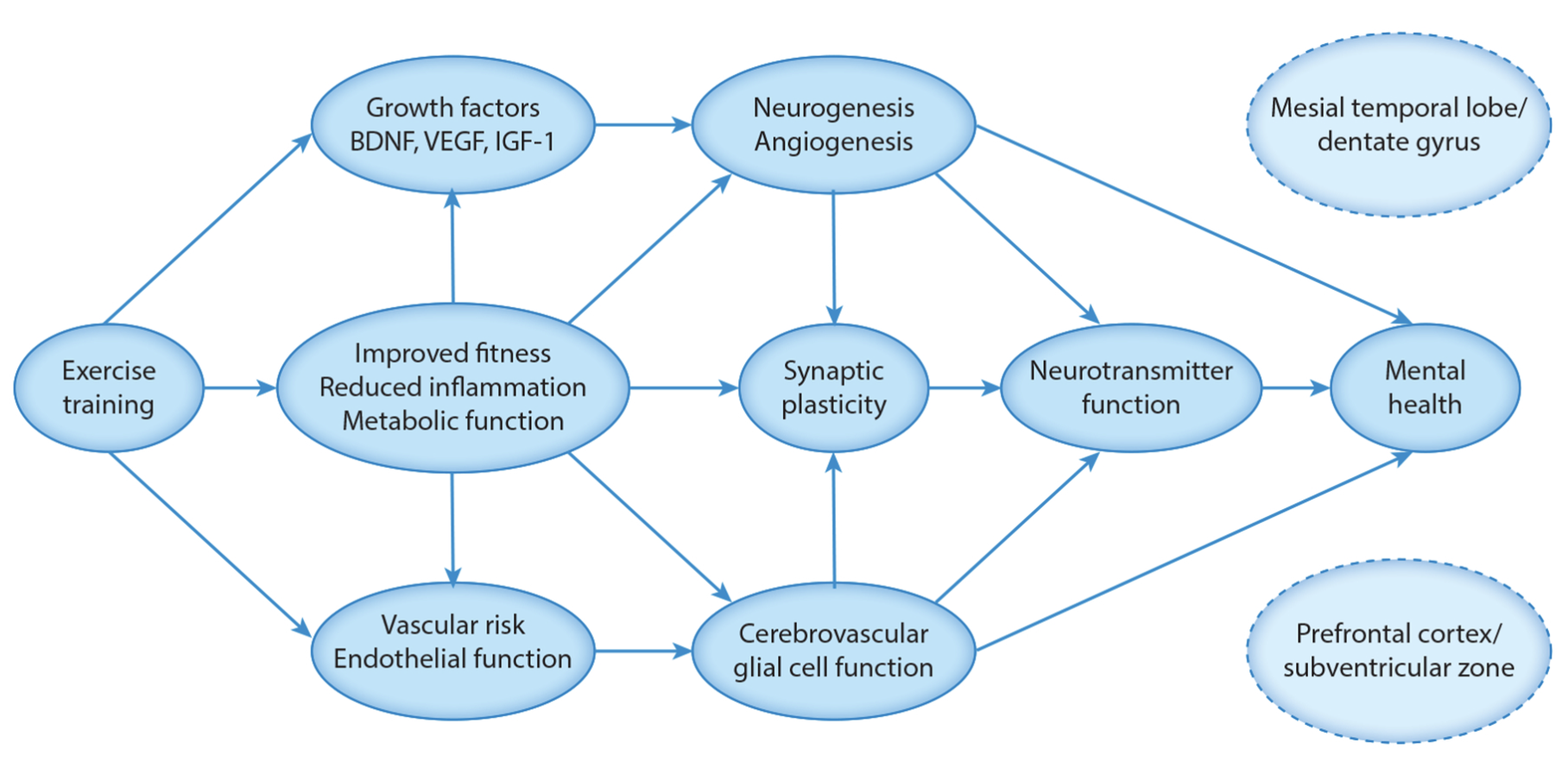

One mechanism of action may be the effect of exercise directly on the brain. It can increase blood flow to the brain, promote the growth of new brain cells, and enhance synaptic connections, which are essential for cognitive functions.

Studies also suggest that exercise can reduce neuroinflammation caused by neurofibrillary tangles and amyloid deposits in the brain, which are key factors in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s.

Preventive Effects of Exercise

One question about exercise and dementia protection is, how much exercise are we talking about? While there are a number of studies showing that walking 6,000 steps per day or more is associated with a decreased risk of Alzheimer’s, not all older adults are able to engage in that much activity. Is some exercise better than no exercise?

You bet it is.

A 2023 study explored if less exercise was still beneficial, and found that for adults over the age of 50, even a single session of walking 15–30 minutes per week (1,500–3,000 steps or so) looked like it cut dementia risk in half. And people who were able to walk 15–30 minutes almost every day had one-fifth the risk compared to those who didn’t exercise at all.

Some recent studies have looked at how exercise affects brain physiology as well as function. A 2023 meta-analysis of 12 clinical trials found that exercise improved such cognitive skills as global cognition (that’s overall cognitive function — not some super skill at memorizing capital cities on a globe) and executive function (organization and decision-making), but didn’t affect processing speed or short-term memory. (So it probably won’t help to jump up and down if you’ve misplaced your keys.)

The clinical trials also included EEG (electroencephalogram) and fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) assessments that showed that exercise improved how neurons in the brain functioned in response to stimuli.

And in a 2023 review article, researchers noted that exercise can reduce the risk of dementia by decreasing the odds that a person will develop heart disease and diabetes, both of which are linked to mild cognitive decline. It also helps keep blood vessels healthy, making it easier for blood to flow (which can reduce high blood pressure).

On a smaller scale, within the body’s cells, aerobic exercise might help reduce brain inflammation and improve the flexibility of neuronal synapses by releasing compounds with fun names like irisin, cathepsin B, CLU, and GPLD1.

Disease Management

Research also shows that exercise can help people who already have dementia.

One 2022 meta-analysis of 16 clinical trials found that Alzheimer’s patients who exercised 3–4 times per week for 30–45 minutes improved their global cognition after just 12 weeks.

Another 2022 meta-analysis of 15 randomized controlled trials found that 30-minute exercise sessions 3 times a week significantly improved scores on a test called the MMSE (mini-mental state examination) which is widely used to assess cognitive function. (It includes questions about where you are and the current date, as well as tasks such as copying a drawing and writing a short grammatically correct sentence.)

Yet another 2022 meta-analysis (clearly, this was a banner year for dementia-exercise meta-analyses) looked at 22 studies, involving more than 1,600 Alzheimer’s patients, that examined the effect of exercise on cognitive functioning. The aggregate data shows that physical activity improved MMSE scores, as well as the results of other cognitive tests (including one specifically for executive function.)

Why Exercise Benefits the Brain

As we’ve seen, researchers are currently looking for mechanisms by which exercise improves cognitive health and resilience. Two popular ideas are that physical activity reduces the buildup of harmful substances in the brain and that it encourages the growth of new brain cells and connections.

To be more specific, exercise increases the expression of neurotrophic (“neuron-growing”) factors like brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF — we’ll meet it again in a little bit) and vascular endothelial growth factor, both of which are essential for neuroplasticity and cognitive function.

Increased Blood Flow to the Brain

Exercising increases your heart rate, which increases blood flow throughout your body. And that includes your brain. Researchers have discovered that when your brain gets more blood, its metabolism increases.

This is important because people with dementia may have decreased blood flow due to vascular changes (as in vascular dementia), degeneration of nerve cells and blood vessels, and cardiovascular diseases that accompany or precede cognitive decline.

Another factor is a condition known as blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction. The blood-brain barrier is the “security guard” of the brain, keeping out toxins and pathogens while allowing in the compounds that the brain requires to function. When this barrier breaks down or stops working, neurodegeneration and brain shrinking can occur, often well before the appearance of clinical symptoms of dementia.

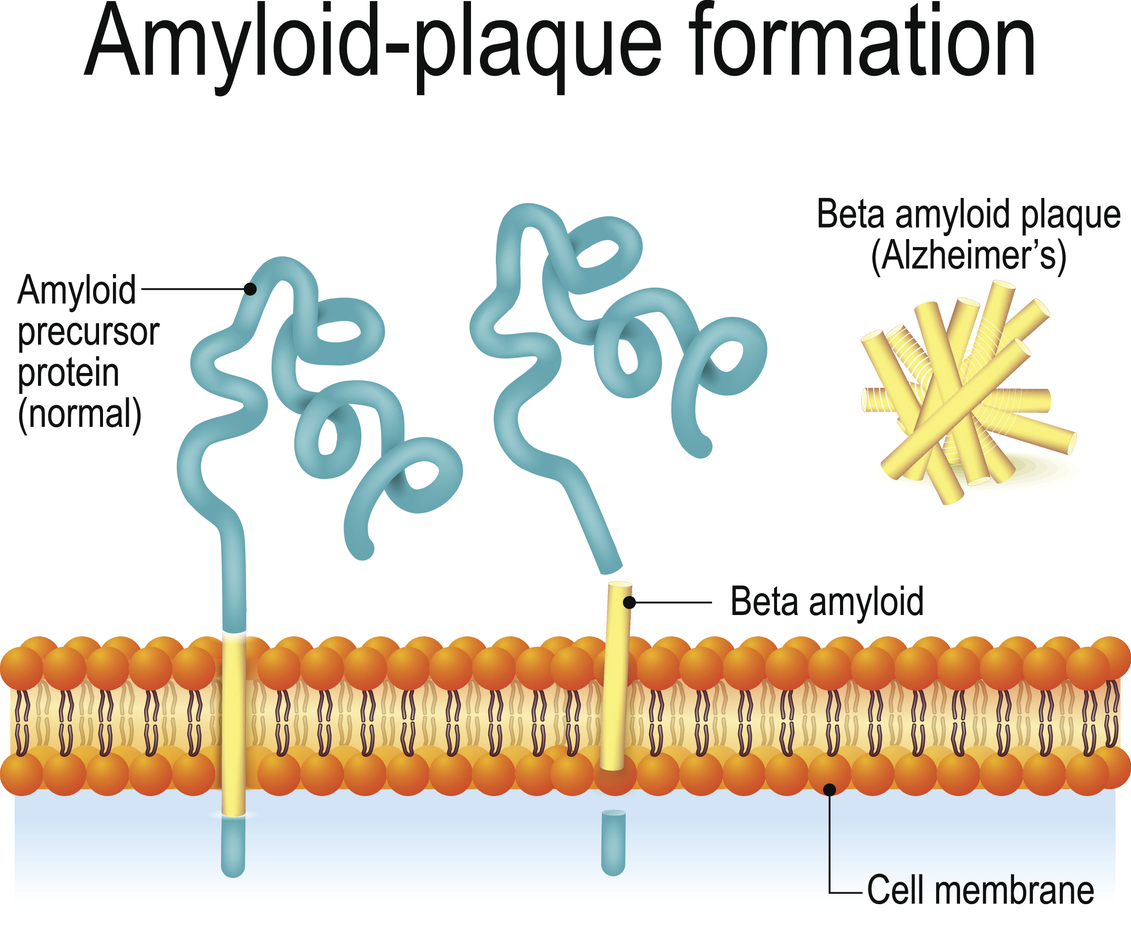

Enhanced Amyloid Beta Turnover

One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease is the production and deposition of the amyloid beta peptide (Aβ, if you want to sound like a scientist) in the brain. Abnormally high levels of this protein, which also can be found in healthy brains, clump together to form deposits that interfere with proper cell function.

Physical activity can help decrease amyloid-beta deposition and increase its clearance from the brain, which may contribute to the prevention or management of Alzheimer’s disease.

Neurogenesis

Meet your hippocampus, a brain region that serves multiple functions — the main ones (and those most related to dementia) include learning, memory, and emotional regulation. (Note to self: Please stop picturing hippos wearing graduation gowns while thinking about the hippocampus.)

Through a process called exercise-mediated hippocampal neurogenesis, healthy brains generate new neurons that get incorporated into hippocampal circuits. It appears that one of the drivers of this process is BDNF, which is known to increase with physical activity.

Alzheimer’s disease disrupts the balance between neurogenesis and neurodegeneration, favoring destruction over building. Exercise can restore the balance, at least to some degree, by combatting neurodegeneration caused by dementia.

Mood Improvement

Mood is affected in many types of dementia, both because of physical changes in the brain and as a reaction to the disease and its impact. People with severe dementia have lower endorphin levels, which are associated with pain relief, stress reduction, and mood enhancement.

Anyone who’s experienced a “runner’s high” or has felt blissed-out on the yoga mat knows that exercise can improve mood by increasing endorphin levels and triggering the release of lots of other “happy juices” (that’s a bit of jargon I dearly wish neurologists would adopt). Among them are serotonin and dopamine, both associated with pleasure and reward.

How Much Exercise Is Beneficial?

There is no set amount or type of exercise that is prescribed specifically for dementia management and prevention. One study found that people between the ages of 40 and 79 who took 9,826 steps per day were 50% less likely to develop dementia within seven years. (When I read the article, I thought, “That’s a weirdly specific number,” until I saw that it was an average.)

Walking is great and accessible to many people, but it’s far from the only option. A 2022 study of a cohort in the UK found that everything from vigorous exercise to housework-related activity reduced the risk of several types of dementia.

And exercises that are good for the heart are also good for the brain. They trigger the body to produce more nitric oxide, a key chemical that dilates blood vessels and improves blood flow — and that is low in Alzheimer’s patients.

Health organizations like the US CDC and the UK’s Department of Health recommend that adults get 150 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity a week, and 2 days of muscle strengthening activity.

Researchers also agree that adults should aim to minimize their sedentary time, as being physically active at any level is better than no physical activity at all. There’s good evidence, as we’ve already seen, that even light activity makes a difference when it comes to dementia prevention.

That said, moderate- and vigorous-intensity physical activity seems to have the most benefit. And older adults may also want to add balance-improving exercises at least twice a week.

Exercises for Dementia and Alzheimer’s Management and Prevention

Dementia prevention is not limited to one activity or even one type of activity. This makes sense since the point of exercise is to move, raise the heart rate (even if only slightly), and engage with the physical world.

A 2022 review and meta-analysis titled “Leisure Activities and the Risk of Dementia” found that a wide variety of activities could lower dementia risk. These included “walking for exercise, hiking or excursions, jogging or running, swimming, stair-climbing, bicycling, using exercise machines, playing ball games or racket sports, participating in group exercises, performing qigong or yoga, performing calisthenics, and dancing.”

The researchers’ conclusion, given the breadth of possibilities, was, very scientifically, for people to “do the exercise that you like.”

There are four main categories of exercise to choose from in building your anti-dementia movement protocol. These include aerobic exercise, strength and resistance training, balance exercises, and whole-body vibration exercise.

Aerobic Exercise

As we’ve seen, anything that benefits the heart benefits the brain. And one of the best ways to take care of both (and pretty much every other part of your body) is a regular regimen of aerobic exercise — that is, movement that raises your heart rate.

According to the WHO (the World Health Organization, not the guys who did Tommy), aerobic activity should be performed in sessions of at least 10 minutes, with the aim of getting to 150 minutes of moderate exertion or 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity per week.

These may include any of the following, as well as similar activities:

- Brisk walking

- Running

- Dancing and aerobics classes

- Basketball

- Biking

- Swimming and water aerobics

- Hiking

- Tennis or table tennis

- Gardening

- Household chores (I have a feeling my wife is going to love reminding me of this one!)

Some researchers distinguish between open-skill and closed-skill exercises for dementia prevention. Open-skill exercises, which require participants to make active decisions and adapt to unpredictable situations, appear to be more effective in maintaining cognitive function. Sports like tennis, table tennis, badminton, and all ball sports are examples of open-skill exercises.

Closed-skill exercises include using a treadmill, stationary bicycle, or other aerobic machine, or even walking on an even surface. (And no, I don’t recommend dodging traffic on the freeway to make your morning walk more challenging.)

Strength and Resistance Training

Muscle size and strength are strongly associated with good cognitive health. Some studies show improvements in memory immediately after a single session of weight training. There’s compelling evidence that challenging and strengthening muscles positively affects both cognitive performance and brain physiology.

Here are some forms of resistance training that have been shown to reduce the risk of dementia:

- Dumbbell exercises

- Weight lifting

- Using gym equipment

- Calisthenics (push-ups, planks, sit-ups, etc.)

- Using resistance bands

Balance Exercise

While exercises designed to challenge and improve balance haven’t been proven to improve cognition, they do have the benefit of reducing falls in people with mild to severe dementia. This matters because people with mild cognitive impairment fall about twice as often as people who are not cognitively impaired.

Balance exercises include, among other things:

- Yoga and chair yoga

- Tai chi

- Step-ups

- Knee lifts

- Standing on one foot

And here’s a nice article on other exercises for seniors looking to improve their balance.

Whole-Body Vibration Exercise

Machines that gently vibrate the whole body can mimic the effects of exercise on muscle fibers and bones. Whole-body vibration exercises can induce changes at the cellular and even molecular levels, and are known to provide neuromuscular, respiratory, and cardiovascular benefits.

They have also been shown to improve cognitive function in people with dementia. This is an especially exciting option for people with limited mobility for whom more vigorous forms of activity are impossible. If that sounds interesting, check out the Editor’s Note about the Power Plate below.

Get Moving — Your Brain Depends on It!

There’s a compelling relationship between physical activity and brain health, particularly as it relates to dementia prevention and management. Exercise plays a vital role not just in enhancing physical well-being but also in bolstering cognitive functions, delaying the onset of dementia, and mitigating the effects of neurodegenerative diseases. From aerobic exercises to strength training to balance activities, the variety of beneficial physical activities suggests that incorporating any form of regular exercise into one’s lifestyle can significantly contribute to brain health.

While the exact amount and type of exercise that’s ideal for each person may vary, the overarching message is clear: Staying active at any level is preferable to inactivity. Embracing exercise as a preventative and therapeutic tool in the fight against dementia offers a hopeful pathway.

And if you’re a younger person reading this and thinking, “OK, I’ll start exercising when I hit my 60s,” you may want to start sooner. Researchers in Australia measured the fitness levels of a group of children in 1985 and then followed up more than 30 years later. They reported in 2022 that the kids with the highest fitness levels turned into adults with the highest levels of cognitive functioning. It’s never too early to take charge of your health destiny!

Studies show that whole-body vibration may also be beneficial for cognitive health. That’s why it’s now being used by some of the world’s leading doctors, hospitals, professional athletes, and actors, like Serena Williams and Morgan Freeman. Click here to learn more and take advantage of a special limited-time discount for Food Revolution Network members.

If you purchase through that link, Power Plate will contribute a portion of the proceeds to support Food Revolution Network’s mission. (Thank you!)

Tell us in the comments:

- Which exercises might you add to your regular routine to protect your cognitive health?

Featured Image: iStock.com/adamkaz