One of the most famous historical “dirty jobs” was food tester. Because poison was such a popular way of killing monarchs, food testers were employed to nibble at the royal dishes and sip the royal beverages. If they lived, the ruler commenced to dine. If they died, well, somebody would fetch another dish and another tester.

It didn’t always work out — according to some historians, the food tester for Roman emperor Claudius turned out to be his murderer, slipping him some poisoned mushrooms from the emperor’s not-so-loving wife, Agrippina.

These days, food testers are pretty rare, if they exist at all. But that doesn’t mean that food isn’t potentially dangerous anymore. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that globally, 600 million people get food poisoning every year, with 420,000 dying.

It’s not just a problem in low-income nations, either. According to the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), 48 million people in the United States get sick from food every year — roughly 1 in every 7 people. More than 100,000 are hospitalized, and 3,000 die.

The way that food is handled, prepared, and stored can determine whether it adds or takes away from life and health.

Sometimes, food safety is compromised somewhere along the supply chain. Examples include crops irrigated with contaminated water, food transported at the wrong temperature, and cross-contamination in a processing facility.

Upon the discovery of possible contamination, the government typically issues a food recall. But regulatory agencies can’t protect you from contamination that occurs after you’ve purchased the food — like, things that can happen when you’re preparing it at home.

So how can you ensure that the food you’re preparing for yourself and your family is safe to eat?

In this article, we’ll look at some of the principles of food safety, how to keep food safe when processing and preserving it at home, and how else you can protect yourself from foodborne illness.

What Is Food Safety?

According to Food Safety magazine, food safety involves a set of practices and procedures designed to ensure that food is handled, prepared, and stored in a manner that reduces the risk of foodborne illnesses.

What are the Health Risks of Unsafe Food?

Foodborne illnesses (aka food poisoning) caused by pathogens like salmonella, E. coli, listeria, and norovirus can cause symptoms ranging from mild gastrointestinal discomfort to severe dehydration, organ failure, and even death.

Common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and fever. And these symptoms may occur within minutes of eating the offending food (which makes diagnosis much easier) or weeks later — in which case the illness may be incorrectly attributed to some other cause.

Food poisoning causes the most harm to vulnerable populations. These include infants, young children, pregnant women, the elderly, and individuals with weakened immune systems — all of whom are more susceptible to foodborne illnesses.

While most people think of food poisoning as a single, acute event, tainted food can also contribute to the development of chronic disease.

Long-term exposure to certain contaminants in food can cause or exacerbate conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis (a form of arthritis of the spine), joint diseases, kidney disease, cardiac and neurological disorders, and disorders of the digestive tract.

These contaminants can enter the food supply at any point, including during growing, processing, packaging, transportation, and storage. Pesticides found in food can also compromise long-term health, as can forever chemicals found in plastic packaging, storage containers, and canned goods.

Heavy metals such as cadmium and lead, which are often present in foods like chocolate, are also unsafe, even in small amounts.

The Rise of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

Thanks to the overuse of antibiotics, particularly in modern Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (factory farms), more and more animal products contain bacteria that are resistant to antibiotics. Two of the most common foodborne pathogens, Salmonella and Campylobacter, cause 660,900 antibiotic-resistant infections in the US each year.

The US federal government tests supermarket meats to track trends in bacteria and resistance. Recent FDA testing data reveals that 73% of bacteria found on ground turkey were resistant to tetracyclines, the most widely used antibiotic in farm animals and essential for treating serious bacterial infections in humans.

Moreover, one in five strains of Salmonella in chicken meat was resistant to amoxicillin, the second most frequently used antibiotic on farms and the top medication prescribed to children. The CDC reports that one in every 25 packages of raw chicken is contaminated with Salmonella.

E. coli has been found in 40% of raw chicken samples tested, but beef is the most common source of E. coli exposure for humans, potentially causing up to 85% of urinary tract infections each year. It’s also a major part of the Salmonella risk.

If you avoid animal products, you dramatically reduce your risk of sickness or death from Salmonella and E. coli exposure.

What about fruits and vegetables? Don’t they sometimes contain E. coli, too? Yes, though last I checked, romaine lettuce and tomatoes don’t have intestines. The only way any vegetable can be linked to E. coli is to be contaminated by the feces of animals.

This contamination often happens when a factory farm is upstream (or up-manure) from a vegetable farm. Animal waste, rich in pathogens like E. coli and Salmonella, can run off during a rainstorm or seep into underground aquifers, ultimately getting into nearby water systems that spread the pathogens elsewhere.

These resilient pathogens can spread not only to raw meat products but also to produce (via water or soil contamination) and cooking surfaces during food preparation. When you consume this contaminated food, that’s when you may get sick.

How Can You Keep Your Food as Safe as Possible?

Obviously, you don’t have much control over whether the cacao pods in your chocolate chips were dried next to a highway filled with trucks burning leaded fuel or whether the organic lettuce you bought at the supermarket was grown in fields contaminated with runoff from a nearby hog farm.

Where you do have some power to keep your food safe is in your kitchen. Food safety educators emphasize the “Four Cs” — four principles of food safety to keep in mind and follow. (And no, the “three-second rule” isn’t one of them.)

The Four Principles of Food Safety

1. Clean

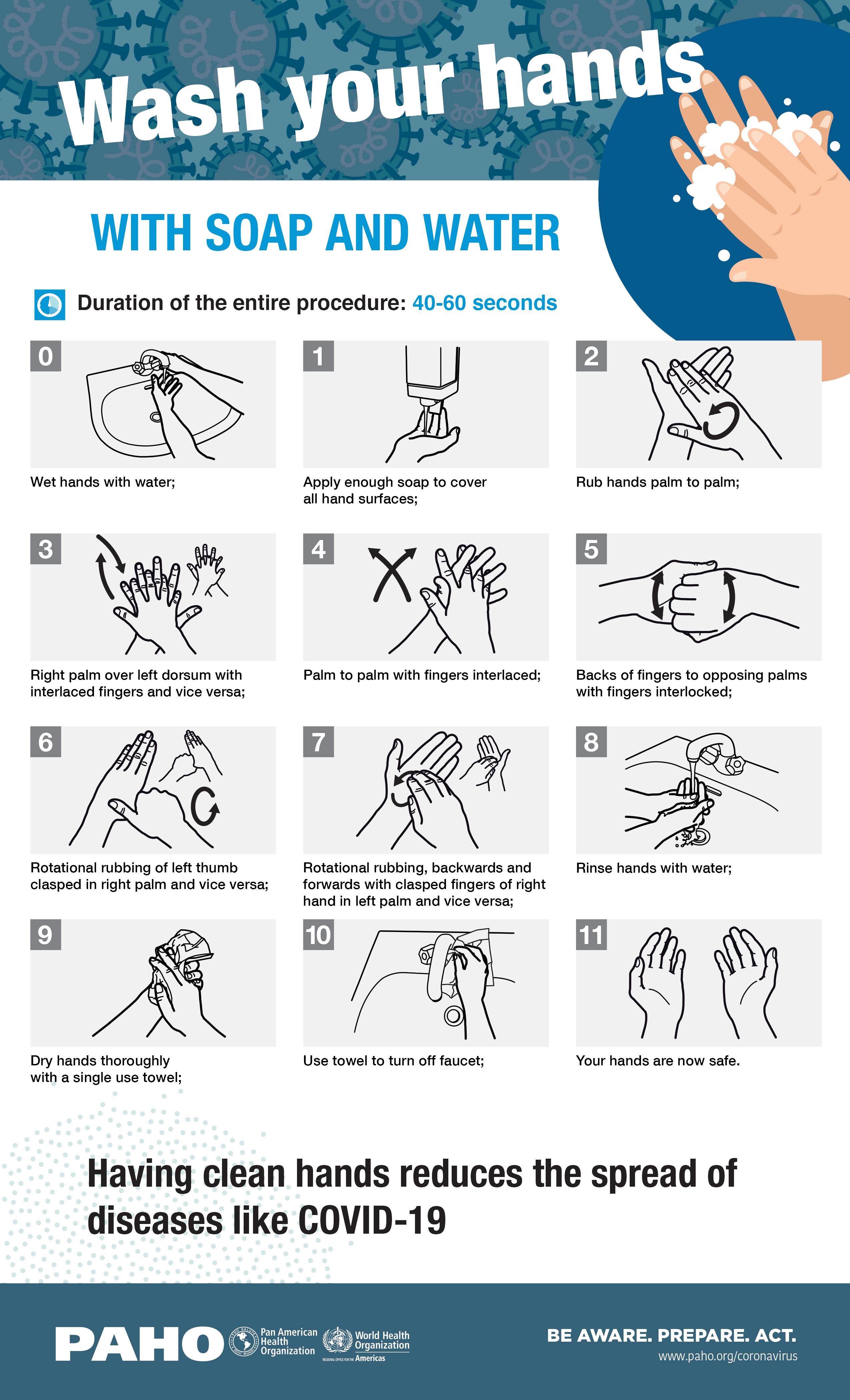

This means washing your hands before, during, and after preparing food — and before eating. This is especially important if you handle raw meat (and one reason plant-based eaters may be at a lower risk of foodborne illness than omnivores).

At the risk of sounding obvious (and putting gross images in your head), you should wash your hands after using the bathroom, changing diapers, and handling pets. (That goes triple for changing your pet’s diaper in the bathroom, I suppose.)

And hand washing is itself a bit of a science. Experts tell us to use soap, sing “Happy Birthday” while scrubbing (if you don’t self-report, you don’t have to pay royalties), and make sure to lather and rinse the entirety of both hands, including the back of your hands, nails, and spaces between the fingers.

Also, wash your utensils, cutting boards, and countertops with hot, soapy water after preparing each food item. Wash fresh produce to remove contaminants, including any pesticide residues. The best method uses baking soda and water. Here’s an article on how best to wash fresh produce.

2. Contain

It would actually make more sense to use the word “separate,” but then our 4-C mnemonic would be lost.

One category for containment is any food containing allergens, which can cause severe allergic reactions in susceptible people. To prevent cross-contamination of allergens, keep foods containing them separate from the rest of your food.

That means using separate kitchen tools, pots, pans, blenders, and so on. In cases of severe or life-threatening allergies, it may be wise to remove the allergen from your home altogether.

Another category for containment is problematic or potentially contaminated foods — especially raw meat, poultry, and/or seafood. You can reduce the risk of cross-contamination by using one cutting board or plate for any raw animal products, and a separate cutting board or plate for produce, bread, and other foods that won’t be cooked.

Of course, this risk is moot if you don’t bring meat or eggs into your home at all. Which reminds me: Scientists who study food safety recommend treating plant-based meats the same as regular meat, using a separate cutting board, or washing the cutting board thoroughly before using it for anything that will be eaten raw.

That speaks to a more fundamental principle of not mixing raw and cooked foods unless the raw ingredients are going to be cooked.

3. Cooking

Any foods containing animal products should be cooked to a safe minimum internal temperature. To be safe, apply this rule to casseroles, leftovers, and plant-based meats like ground beef analogs. If you’re heating food in a microwave oven, check for cold spots before serving.

Some plant-based foods should always be cooked. These include mushrooms (due to the compounds agaritine and lentinan); potatoes (thanks to the presence of solanine); and beans — even fresh ones — such as broad beans and red and white kidney beans (because of a plant protein called hemagglutinin).

4. Chill

Bacteria can multiply rapidly at room temperature. The full “danger zone” for bacterial growth is actually between 40°F and 140°F (or 4°C and 60°C for you metric fans). To keep bacteria from spoiling perishable food, try to get it refrigerated within two hours after taking it off the heat or one hour if your ambient temperature is higher than 90°F (32°C). The important thing is to get it to cool rapidly so it reaches the safe refrigerator-storage temperature of 40°F or lower, where bacterial growth is inhibited.

I don’t recommend putting a large pot or container of hot food directly into the refrigerator or freezer, though, because it can actually warm everything else in there (and make your refrigerator or freezer work extra hard, driving up your electricity bill). One way to help food cool quicker is to divide it into smaller portions (ideally in shallow containers) or spread it out on a baking sheet prior to refrigerating (a good way to cool large batches of whole grains).

If you’re serving food at social gatherings, it might have to sit out for hours while guests help themselves. You can keep the internal temperature of hot dishes at 140 °F or higher by using chafing dishes, slow cookers, or warming trays. You can keep cold dishes below 40°F by nesting them in bowls of ice or using small serving trays and refilling them often.

A safe setting for your refrigerator is below 40°F and for your freezer, 0°F or below.

You can safely thaw frozen food in the refrigerator, in cold water, or in a microwave. However, food safety experts warn against thawing frozen food on a counter because bacteria multiply quickly in the parts of the food that reach room temperature (the outside can get quite warm even as the center remains solidly frozen).

If you have leftovers, it’s recommended to cover them, wrap them in airtight packaging, or seal them in storage containers. Most leftovers keep in the refrigerator for three to four days or frozen for three to four months (sometimes longer).

Other Tips for Optimal Food Safety in the Kitchen

Preserving and Processing Foods at Home

There are several methods of preserving and processing foods that can lead to bacterial growth unless they’re done properly.

Sprouting

Sprouting grains and seeds, for example, can lead to microbial contamination. Raw alfalfa and bean sprouts are particularly vulnerable, and home sprouts also present a slight risk of contamination if you’re not careful.

Experts recommend washing your hands and sterilizing your sprouting materials between batches. You can also lower the risk of microbial contamination by soaking the seeds in a solution of food-grade hydrogen peroxide diluted to 3% for up to five minutes. Then, rinse the seeds with cool running water. Not only does the hydrogen peroxide reduce the risk of pathogens, but it can actually help increase germination rates. (For more on why sprouting is so wonderful and how to do it effectively, see our article here.)

Fermenting

Fermenting foods can also expose them to bacteria and mold if it’s not done properly. Common mistakes include too much exposure to air, using a not-quite-clean container, skimping on the salt, and fermenting at the wrong temperature.

Canning

Canning is a way to turn surplus fresh food into stored calories and nutrients for later. Home canning requires a sterile environment to prevent contamination. Once canned correctly, the food must be stored in the right temperature range and sealed with an air-tight lid to prevent the growth of pathogens like botulism and mold (also known as mycotoxins). Visit the canning guide from the National Center for Home Food Preservation for best practices.

Dehydrating

Humans have also been dehydrating food for thousands of years — at least since someone forgot a banana on a rock on a hot day and came back in the evening to enjoy the world’s first banana chip. And we’ve also probably been getting sick from improperly dehydrating food for about the same length of time.

If a location is too humid, produce can mold before it dries sufficiently. Vegetables, in particular, can spoil during sun drying. To prevent mold from growing, make sure that foods you dehydrate are completely free of moisture before storing. To dramatically increase dehydrated foods’ longevity, store them in the freezer. (For more on dehydration and how to do it well, see our article, here.)

Buying Organic

One consistent tactic to improve the safety of the food you eat is to choose organic whenever possible. Organic foods are free of chemical preservatives, chemical flavorings, synthetic coloring, sewage sludge (yuck, right?!), irradiation, genetic engineering, and most synthetic pesticides and fertilizers.

They also have lower levels of toxic metabolites, including heavy metals such as cadmium, synthetic fertilizer, and pesticide residues. And if you eat organic foods, you’re also probably reducing your exposure to antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

If you can’t access or afford organic produce, make sure to wash it properly to reduce your exposure to pesticides and other surface contaminants.

Avoiding Plastics: Packaging

Plastic containers often contain BPA and other harmful compounds, including those known ominously as “forever chemicals” that can leach into the food they hold.

These substances can have endocrine-disrupting and carcinogenic effects, meaning they can mess with our hormones and cause the development and progression of cancer.

To minimize the leaching of plastic chemicals into foods, avoid microwaving foods in plastic containers, and wait for food to cool before packing it in plastic. Acidic foods and very fatty and oily foods leach more plastic than others, so use glass jars to store tomato sauces and similar products. Or even better, replace plastic containers with those made from glass, stainless steel, or silicone.

For more tips on avoiding plastic, check out our article, Is a Plastic-Free Lifestyle Possible? Tips for Reducing Your Plastic Footprint.

Cookware

Another class of chemicals that can harm our health is in many of the popular brands of non-stick cookware. The compounds, collectively known as PTFEs, are released by heat, so you can avoid ingesting them by not cooking with Teflon and similar brands.

If you want to know more about what’s the healthiest cookware on the market, check out our article, The Ultimate Guide to Safe Cookware: How to Choose Wisely for Your Health.

Seafood

Another source of plastic in our diets and tissues is the oceans. Plastic trash that gets into waterways ends up as microplastics — pieces so small they can be swallowed by fish and work their way up the aquatic food chain.

If you eat seafood, then, unfortunately, you’re placing yourself at the top of that chain. A 2024 study found concerning concentrations of microplastics in the testes of every single male participant (23 out of 23), which some scientists think is linked to plummeting sperm counts over the past half-century.

Avoiding Heavy Metals

We’ve seen that choosing organic foods can reduce your exposure to toxic heavy metals, but that’s not the only strategy at your disposal. Mercury is often found in canned tuna and other seafood, so not eating fish can keep the silver stuff out of your body.

Ground turmeric is also a potential source of lead contamination, which is a real pity since the root itself can be such a health powerhouse. You can read all about turmeric and how to take advantage of its benefits while minimizing its risks in this article. (If you just want to click through to a brand of turmeric powder that we like because of the company’s transparency and rigorous testing protocols, here’s a link to New Harvest Turmeric from Burlap & Barrel.)

Chocolate is another theoretically healthy food that is often contaminated, in this case, with lead and cadmium. Sadly, the “healthiest” chocolates (those with low sugar and high cacao content and organic varieties) tend to be the most affected. Here’s a whole article on heavy metals in chocolate and ways to protect yourself.

Another heavy metal, arsenic, often contaminates rice. To find out which types of rice are least affected and how you can prepare and cook rice to minimize your exposure, check out our comprehensive article, Arsenic In Rice: How Concerned Should You Be?

Expiration Dates

Sometimes food is perfectly safe to eat right now but won’t be later. That’s the idea behind the sell-by, best-by, and use-by dates on food labels. It’s a confusing system, though; most foods can still be eaten safely after the expiration date, but how long after depends on the product and its storage.

A use-by date is usually the most important for telling if a food is past eating. But you can also use your eyes and nose to discern regular old food from old food with a grudge and the bacteria to back it up.

Oils and other compounds in foods can degrade rapidly, especially if exposed to heat. If you’re about to eat or serve something that smells rancid, is rotten, or has mold on it (excluding foods like tempeh that are supposed to contain a safe form of mold), don’t eat it — even if it hasn’t yet reached its expiration date.

Lean on the Side of Safety When it Comes to Food

Proper handling, preparation, and storage of food at home can significantly reduce the risk of foodborne illnesses. While government agencies issue recalls when food safety issues arise along the supply chain, individuals must also take responsibility for food safety in their kitchens.

By understanding and implementing the four principles of food safety — Clean, Contain (Separate), Cook, and Chill — you can protect yourself and your family from potential health hazards. Additionally, utilizing best practices when processing food, buying organic, avoiding plastics and heavy metals, steering clear of animal products, and paying attention to expiration dates on packaging can further keep you safe from food contamination.

Tell us in the comments:

- What’s your biggest food safety takeaway from this article?

Featured Image: iStock.com/SARINYAPINNGAM